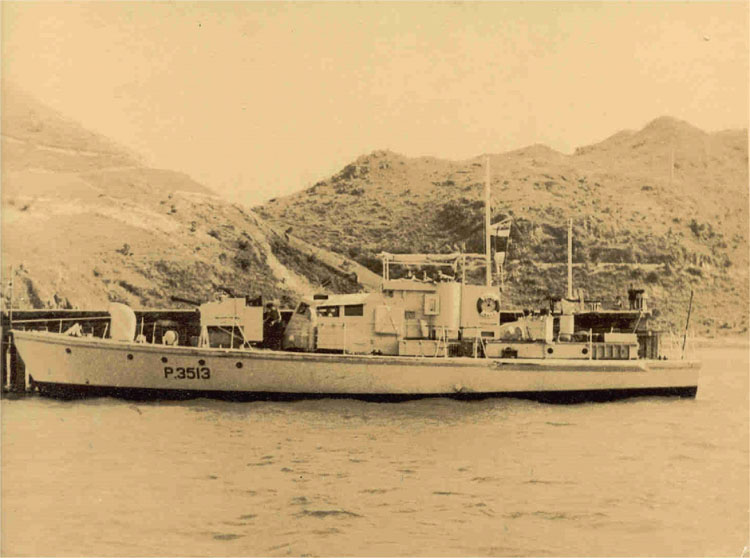

HDML 1383

Anderson Rigden & Perkins, Whitstable 30/12/43

London Gazette 19/12/44 – For good service distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy

- DSC TLt Albert Thomas Victor Kingdon RNVR

- DSM LSea Ernest Alfred Knott LT/JX224401

- MID Tel William Thomas Charville C/JX426286

- MID Engm Louis Caldwell Gray LT/KX160046

London Gazette 3/7/45 – Rescue of survivors of MV GOLD SHELL mined and sunk off the Belgian coast 16/4/45

- MID TLt Albert Thomas Victor Kingdon RNVR

- MID LSea Ernest Alfred Knott LT/JX224401

- MID Ck Richard Cunningham LT/MX224401

Known Crew

- TLt Albert Thomas Victor Kingdon RNVR TSLt HMS St Christopher for MLs 27/4/42 TLt 19/2/43 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 For good service distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy DSC Commanding Officer HDML 1383 27/1/45 Rescue of survivors of MV GOLD SHELL mined and sunk off the Belgian coast 16/4/45 MIDTSLt A P de Nobriga RNVR TSLt 24/8/44 149th ML Flotilla First Lieutenant HDML 1383

- TASLt D N Bromage RNVR TASLt 6/8/43 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 TSLt 6/2/44 20th ML Flotilla Based on Portsmouth ML 123 5/44 Operation Neptune Invasion of Normandy ML 368 21/4/45

- Engm Louis Caldwell Gray LT/KX160046 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 For good service distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy MID

- LSea Ernest Alfred Knott LT/JX224401 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 For good service distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy DSM Rescue of survivors of MV GOLD SHELL mined and sunk off the Belgian coast 16/4/45 MID

- AB Percy John Hulcoop JX444598 Ord HMS Glendower (Pwllheli) 22/3/43 HMS Valkyrie (Douglas, Isle of Man) 12/6/43 HMS Orlando (RTF) (Greenock) 9/7/43 HMS Valkyrie 23/7/43 HMS Hornet 1/10/43 On passage 25/10/43 HMS Braganza (Bombay) 30/11/43 AB HDML 1383 1/4/44 HMS Collingwood 5/6/45 HMS Valkyrie 30/6/45 HMS Excellent 18/8/45 HMS Ramillies 20/9/45 –

- Tel William Thomas Charville C/JX426286 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 For good service distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy MID

- Ck Richard Cunningham LT/MX224401 149th ML Flotilla HDML 1383 Rescue of survivors of MV GOLD SHELL mined and sunk off the Belgian coast 16/4/45 MID

TSLt de Nobriga RNVR (First Lieutenant)

TSLt de Nobriga RNVR (First Lieutenant)

Wartime Activities

- 149th ML Flotilla

- 1/44 Shakedown cruise on the east coast: Hartlepool, the Tyne, Leith, Buckie and Inverness, through Caledonian Canal, Oban, on to Falmouth.

Part of Task Force O with HDML 1387 and 11th ML Flotilla - 6/44 Operation Neptune Invasion of Normandy

149th ML Flotilla

ML1295, ML1309, ML1383, ML1387, ML1389, ML1391, ML1392, ML1393, ML1407, ML1409, ML1421. ML1422 - 5-6/6/44 Channel Marker at Omaha Beach on D Day

From the Operational Orders for D Day…

HDML 1383 and HDML 1387 are identified as the Channel Identification Group.

They are to proceed from Portland independently in time to reach Approach Channels 3 and 4 respectively by H Hour – 13. The approaches are marked by FH 830 acoustic beacons previously laid by ML 147, ML 151 and ML 198 Operation Enthrone

HDML 1383 and HDML 1387 are to transmit 3 or 4 as appropriate at 30 second intervals on a shielded blue signal lamp through the night. By day they are to fly a large international code numeral flag. HDML 1383 and HDML 1387 are to remain on station until 2300 on D Day.

Distributing instructions in the assault anchorage after the first landings in Normandy.

- 2/7/44 HDML 1383 and HDML 1387 at Falmouth.

Attached to minesweeping forces clearing Dieppe and Ostend. - 16/4/45 MTB 476 and ML1383 rescued survivors of MV GOLD SHELL mined and sunk off the Belgian coast in position 51.22n 02.55e

Post War History

- Fast Despatch Boat = FDB86

- 10/46 Sold

Special Equipment Fitted for D Day

GEE System – Vessel was provided with an RF #27 unit capable of receiving special frequency (XF) transmissions from the Southern GEE Chain. Coding schedules were supplied separately at a late date. Special fine lattice charts covering the assault area were also provided sealed. They were not to be opened before receipt of code message “OPEN ONWEST/O”.

DECCA System – Vessel provided with Type QM gear. This system was not encrypted. Special fine lattice charts covering the assault area were also provided sealed. They were not to be opened before receipt of code message “OPEN ONWEST/O”.

Radio Beacon 78T – To be switched on when the beacon position was reached and transmitted on 340 degs True. These transmissions were to continue until H Hour (13 hours being the approximate battery life of the device). Type 78T transmissions could be picked up by Radar Types 286 and 291 fitted to some approaching units at 15 miles (if within the beam) or at less than 4 miles (outside the beam). Receivers were tuned to 214 Mega cycles, producing a display of a string of needle like pulses giving a code bletter at approximate one minute intervals. HDML 1387 transmitted the letter “C”.

FH-830 Acoustic Beacon – Type 134 Asdic could receive beacon transmissions. HDML 1387’s beacon was set on High Tone with a two second repetition rate

Personal memoir of Engm Louis Caldwell Gray LT/KX160046…

“I met my new commanding officer, Lieutenant B.Kingdon RNVR in London and we travelled together to the builders’ boatyard where we saw her: HDML 1383.

What a contrast with ‘HMS Memento!’

She was 72 sleek feet long with everything new and shining. She was fitted throughout in smooth Mahogany to very high standards of workmanship. It was a joy to have my own Engine Room to order as I wished. The twin Thornicroft diesels were responsive and easy to manage, and the auxiliary engine for lighting and battery charging was a sturdy single cylinder Gardiner diesel which I was to meet ten years later pumping water from the Kafue River in Africa.

For once in naval construction, thought had been given to accommodation.

The crews’ quarters were for’ard as also was the Galley, with an internal ‘companion way’ to the enclosed Wheelhouse. Behind the Wheelhouse was an open Bridge where a hatchway led down to the Engine Room, while another gave access to the ‘after quarters.’ These comprised a Cabin with its own toilet facilities shared by myself with the Coxswain; across the ‘companion way’ was a Radio Cabin and aft of that a well fitted Wardroom.

As an Escort Vessel we were quite well equipped.

The 20mm Oerlikon aft was excellent. Two racks of ‘depth charges’ looked purposeful although we never dropped any in anger. The Bridge carried twin Vickers .303 machine guns on each wing. On the ‘foredeck’ we at first had a three pounder gun, from which the shell would sometimes scream into the far distance, or cause consternation by almost dropping out of the muzzle. Once it was replaced by another Oerlikon we were more effective. In my years afloat I never fired a weapon of any sort, nor was I ever hurt by one.

The Crew was typical of the those found on most small craft with the majority being in their late ‘teens’ or early twenties plus an occasional older hand or two but almost none with any previous seagoing experience.

Our Commanding Officer known colloquially among the crew as ‘Bert,’ was a quiet self-contained man who had worked with the BBC before the war. The First Lieutenant, sub-Lieutenant de Nobriga RNVR, inevitably known as ‘Nobby.’ was fresh out of ‘university. He was young and keen for activity and new experience and we became as close to being friends as was practicable .At the end of the commission and after demobilisation, he arrived at my home in West London one day in a dashing red MG Sports Car and we renewed acquaintance. The Coxswain, Ernie Knott was a ‘street wise’ character from the ‘East End’ of London and at thirty four was the oldest man aboard. He possessed a fund of earthy aphorisms which tended to stick in the memory and a street philosophy which sometimes shocked younger crew members. I quote, ‘A standing prick has no conscience,’ which seemed appropriate for the seaman mentioned on HMS Memento.

The seamen, stokers, signallers, cook, AZDIC, signals ratings and gunners were all late ‘teens’ or early twenties. One, ‘Tich’ had the face and physique of a youthful boy but with adult tastes which gave him great success with young girls. Another seaman had been a shop assistant before joining the Navy where he proved to have a natural talent with guns. With a 20m Oerlikon he was a deadly shot and unless forcibly restrained would pick a soaring seagull out of the sky as easily as swatting a fly. He was an oddity in another way by completely disproving the saying, ‘There is no smoke without fire.’ He was a compulsive liar who told the most blatant and pointless lies for no obvious reason or advantage; all they ever earned him was punishment. One of my ‘stokers,’ a competent and practical man fresh from a Manchester mill, was engaged to a girl at home and on hearing we were to spend several days in port on one occasion, he arranged for her to visit. As he prepared to go ashore there was much loud speculation and ‘back-chat’ on the Messdeck as to how he could possibly entertain her in such a ‘dead and alive’ place. He stopped all speculation by appearing stark naked from the ‘Heads’ and displaying an astonishing endowment; it was quite remarkable.

But enough!

They came from all walks of life with their own weaknesses, strengths and moral attitudes but to the Navy they were all seamen.

In the January of ‘44 we carried out a ‘shake-down’ cruise running the full length of the East Coast, during which a series of particularly severe Winter gales drove us into the shelter of a variety of ports. We lay in Hartlepool where during a run ashore we found the biggest Dance Hall I have ever seen. On runs ashore the Crew usually went as a body, except for ‘watchkeepers,’ and almost always headed for the local dance hall in search of company.

We ran into the Tyne for shelter where I was able to contact friends not seen for years. In the Firth of Forth we were storm bound for several days and I was able to renew family ties in Edinburgh with an uncle and aunt. Discipline was always easier on small ships and by bottling’ my daily tot of navy rum I brought a gleam to my uncle’s eye when I presented the elixir. I also took opportunity to get away from the coldest East wind I had ever known and slipped across to Paisley to visit ‘Marion,’ a girl whose name, address and photograph I had found inside a tin of Dobie’s Four Square pipe tobacco. This was something frequently done by girls working in tobacco factories making up ‘duty free’ issue for naval ships. It was a harmless practice which brightened the lives of many sailors: and was illustrative of a time when all kinds of people reached out desperately for friendship and reassurance in what were very uncertain times. I had dinner with Marion’s family and paid a second visit but like all sailors eventually sailed away.

We left Leith but were soon driven to shelter in Buckie Harbour where we experienced at first hand the full, drab, tedium of a Scottish Sunday. We moved on to Inverness, and rather than face the brutal ‘tidal races’ of the Pentland Firth in winter we entered the Caledonian Canal to cross to the West Coast. At a small shop halfway through the canal I met Nescafe powdered coffee for the first time. I enjoyed the next leg of the journey for we lay in Oban for several days. Then south to Falmouth.

At first we operated largely out of Dover which after years of shelling by the big guns on the coast of Calais was a desolate place and we tended to spend our ‘shore leave’ in Folkestone: but as plans for the invasion of Normandy began to take shape we grew to know the English Channel and other channel ports very well. During the months leading up to D.Day we undertook many and varied duties, one of the most interesting being as AZDIC escort when PLUTO, the ‘Pipe Line under the Ocean’ was being laid for the purpose of providing a continuous supply of fuel to the invading forces once ashore.

Nearer the day we were fitted with specialised navigation equipment and, with additional crew aboard, sailed under cover of darkness for a point off the coast of Arromanches where we anchored, to act as a guiding beacon for the first ships of the ‘invasion fleet,’ even then leaving English channel ports. Dawn revealed the astonishing sight of serried ranks of ships heaving over the horizon and passing in wave after wave, packed to capacity with soldiers and weaponry. It revealed also seemingly endless flights of aircraft passing overhead to saturate the countryside behind the ‘beaches;’ and in full daylight we watched and listened with awe as heavy naval units with famous names hurled salvos of shells at selected targets ashore.

I have often been asked for my impressions and experiences on D.Day and during the days which followed. So often it is the trivia which stays in the mind. I was a pipe smoker and had recently broken mine. I was looking over the side one day when I saw a pipe floating past. Who had lost it and under what circumstances I do not know but after retrieving it I could not bring myself to use it.

My overwhelming impression was of the almost incredible degree of imagination and ingenuity which had been planned into the whole operation. It was evident in almost every experience. Perhaps the first sign was the impressive sight of the slow-moving arrival of the Mulberry Harbour; at first the old cargo vessels which were sunk as ‘block ships’ and then the immense concrete caissons sunk off the open beaches to provide shelter for the invasion force against the raging ‘channel gales.’ and “My word!” how they raged.

My second impression of detailed planning was the sight of ‘landing craft’ fitted out as floating Bakeries and Kitchens serving fresh bread and meals to the crews of the huge number of small craft without the time or facilities to provide for themselves. I felt that if this degree of attention could be paid to such mundane provision, it must surely be reflected across the entire operation and the war must inevitably be won.

With the invasion of Europe firmly under way we resumed our ‘dogsbody’ duties. We pulled a beached landing craft off the Arromanches beach under the cutting tongue of a fierce naval captain, ‘Red Ryder,’ who thought Bert was showing lack of drive, whereas he was really trying to preserve my engines which were never intended to serve in a ‘tugboat.’ We guided vessels between coasts. We escorted a small convoy in company with a Destroyer through a brutal gale to Cherbourg, only to find on arrival the others had been turned back by the weather, and as the senior Naval Officer was not with us the Americans refused us entry and we had to sit out the gale in the ‘outer roads’ where at times I thought the engines would leave their mountings. One night while heading for England we heard an aircraft engine overhead. The craft must have been in trouble because it carried a long tail of fire and fell into the sea. We headed for the spot but found no survivors. It became clear later we must have seen one of the first of the German V1’s, i.e. Flying Bombs.

With the invasion launched and the land action having moved well inland from the Normandy coast our duties varied again. We were attached to a Mine Clearance unit of Fleet Sweepers and after the fall of Dieppe were sent there to see if the channel was clear. I imagine our arrival and return proved something. German ‘pressure mines’ were becoming a problem in the shallow Dutch waters and one Spring morning, after a long and bleak Winter the clouds opened and the sun poured down from a deep blue sky while we acted as AZDIC escort to a flotilla of Fleet Mine Sweepers trying to find an answer to the latest bit of horror which allowed perhaps several ships to pass unscathed but the next would activate the ‘mine.’ The Sweepers were towing a complex structure which was said to exert the same pressure as a twenty thousand ton ship.

We had cleared Ostend early and were moving slowly across a smooth blue sea about three miles offshore. I happened to be on deck getting a breath of fresh air and taking a series of unofficial photographs of a passing convoy of merchant ships making perhaps ten knots towards Rotterdam. Astern of us a despatch Torpedo Boat was leaving a broad creamy wake across the blue water towards England. Suddenly we were shaken by an explosion. The first glance was towards the Fleet Sweepers. Had they found a ‘mine?’ A second explosion turned our attention seawards where the eighth merchantman in the convoy line was burning furiously. Bert, our C.O. obtained rapid permission from the Flotilla Leader to stand by the burning ship. She was quite large, about 15 000 tons carrying a mixed cargo of oil and ammunition. The explosion had caught her amidships which was a blazing inferno. The flames fanned by her continued way through the water left a trail of blazing oil astern.

As we drew near the sight was awesome. The hull plating amidships was white hot and gave an odd impression of transparency while a thin line of flame ran right along the waterline. On deck great gouts of flame and smoke carried the fire astern and a new dimension was added when ammunition began to explode. The only obvious survivors were grouped well forward in the bows. We ran to take them off only to discover two hazards with the curve of the bows forcing us up to the stem where the ship’s way threatened to push us under. We had to complete the rescue in instalments by holding position momentarily while a man or two dropped on to our deck, then sheering off in a tight circle which brought us back under the bows again. We continued until all still alive had been recovered.

The survivors were handed over to the Flotilla Leader of the Fleet Sweepers where a doctor attended to injuries preparatory to getting them ashore to hospital. The burning tanker eventually grounded on one of the sandbanks which littered those waters where it burned for two or three days before turning into scrap iron. For ourselves we earned a repaint because the port side hull and superstructure were well and truly singed; we were just thankful the wooden hull had not caught fire. Someone must have been pleased because awards of a DSC, a D.S.M. and a Mention in Despatches followed.

All campaigns have their quiet periods and during one such Bert, our C.O. must have been talking with his fellow C.O.’s in the Flotilla and made a bet that he had the best maintained Engine Room of them all. The fact is that life at sea is not all sound and fury, there are long periods when hands need to be kept busy and in my case I liked to have engines painted silver, fuel and water lines painted distinctive colours and brightwork highly polished; and emery cloth held against a rapidly spinning propeller shaft produces a shining silver shaft. All these things must have been in Bert’s mind when he issued the challenge, and when the C.O.’s made their inspection of every ship’s engine room they admitted defeat when I removed the bilge covers and exposed dry and white-enamelled bilges. Our winnings gave the crew a good run ashore.

And so it went on week after week until the war in Europe was over.

#We re-equipped for a long voyage in preparation for sailing to the Far East under our own power and to the war against Japan. Then the Americans could not resist the urge to see if it worked and dropped an ‘atom bomb’ on Japan and it did.

Suddenly it was all over leaving a legacy which still haunts us today.

It was all over and HDML 1383 became FDB 84.

We puzzled over the new designation:

Fast Despatch Boat?

Fleet Despatch Boat?

No!

For Disposal Board.

We took HDML 1383 to East India Docks in London, left her alongside the wall and went home. For years I missed her.”